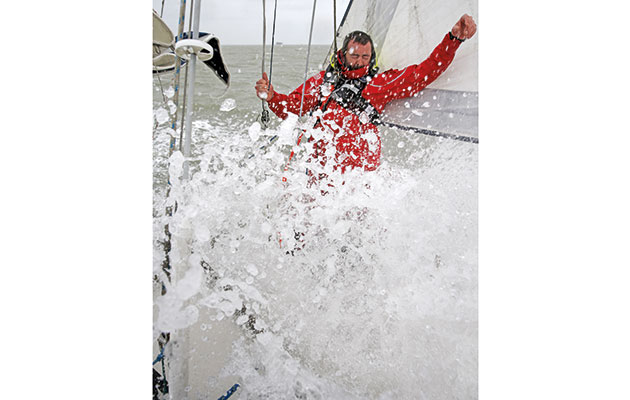

Even clipped on, you can still go over the side. Chris Beeson finds out how a few simple changes can help us to move safely on deck

How to stay on deck and avoid MOB

Chris Beeson

I was sailing aboard Freelance, a Swan 43, in the 1989 Fastnet Race. We were heading north-west across the Irish Sea at night with a reef in the mainsail and the No2 jib when the wind picked up and the skipper called a sail change. Three of us went onto the foredeck, clipped on to the weather jackstay, hoisted the No3 and clawed down the No2. My feet were braced against the leeward toerail and I had an armful of sail when a wave swept the foredeck. When it cleared I found myself half overboard. There was still slack in my tether. The only thing that stopped me from being swept off deck was the stanchion between my legs.

A sail change in a lumpy sea, at night on a wet deck is clearly not without risk, but my behaviour wasn’t cavalier or gung-ho. I’d taken all the appropriate safety measures and yet it was nothing more than a stroke of luck, albeit a fairly painful one, that kept me on deck and possibly saved my life.

The incident came back to me when we reported on the death of Christopher Reddish, skipper of the 38ft racing yacht Lion. The circumstances were similar, but he wasn’t as lucky. Although clipped on to the weather jackstay, he slid unnoticed under the lower lifeline, and was towed alongside at the end of his tether, where he drowned.

The question we have to ask ourselves is this: is going overboard is just one of those ever-present risks involved in sailing, or could we do things differently to improve our chances, not just of staying attached to the boat, but of staying safely on deck?

Reasons to go forward under way are fewer now, but it’s still something we need to be able to do

Fortunately, most modern cruising yachts are set up to reduce greatly the reasons to go forward under way, but some of us still reef and adjust the main outhaul from the mast, the trysail or storm jib may need rigging if you get caught out, an anchor retaining pin may fall out, or a furling line could jam. Whatever the reason, we need to be able to get forward and work safely.

L-R: Ash Holmes and James Hall of safety and deck gear specialist Spinlock ‘sanity-checked’ our suggestions and offered a few others

In an attempt to find some answers, we looked at the deck of a 32ft cruiser, Graham Snook’s Sadler 32 Pixie, and tried to think of how we could make it safer to move around on. We consulted with safety experts James Hall and Ash Holmes from Spinlock and looked for ways to minimise the risk to crew working on deck. Here we share our findings for this particular boat. It’s quite possible that these won’t translate directly to the deck of your boat but the principles underlying each of the changes and suggestions can be interpreted in a way that does.

It’s important to realise that, while safety equipment is regulated by ISO12401, safety itself is not. For example, the ISO standard specifies that a tether must be 2m (6ft 6in) or less. In fact – and as we will show – that is dangerously long for the boats that most of us sail and will not keep you on board. The reality is that the safety of boat and crew is entirely the skipper’s affair. It involves assessing the risk presented by the prevailing and forecast conditions, specifically the ability of boat, skipper and crew to handle them, and acting to reduce that risk, whatever that may entail. It means rejecting conventions and using inventions that you feel ensure safety. Some measures may present other risks, and it’s up to you to judge whether the reduction of one greater risk justifies the increase of a lesser one. You’ve much to think about.

Drowning at the end of a tether

Christopher Reddish slipped off the foredeck and under the lifelines while tethered to jackstays on the 38ft racer Lion

The Reflex 38 Lion was taking part in a race from Cowes to Cherbourg in 2011. Force 7-9 winds and 3-3.5m seas were forecast. After a sail change, skipper Christopher Reddish was on the foredeck to free a changed foresail snagged on a cleat, before taking it aft.

He was clipped onto the windward jackstay on a 1.8m (5ft 11in) tether. Moments later a lifejacket’s strobe light flashed through the foot of the jib and the alarm was raised. He was recovered 16 minutes later but no signs of life were found.

The MAIB report found that recovery was hampered by the conditions, by the fact that no second-in-command had been named, hindering communications, because some crew had missed the man overboard (MOB) drill six weeks earlier, and because recovery of a tethered MOB was not routinely covered by RYA training courses.

What is wrong with the current set-up?

Even on the tether’s shortest leg, a sudden lurch could easily pitch me over the side. It’s obvious that jackstays are rigged too far outboard

Put simply, the problem is that people wearing harnesses with tethers clipped onto jackstays are still going overboard. As I found in the Irish Sea, you can do everything right, take all the standard precautions, and still end up over the side. The standard precautions aren’t up to the job.

If a tether is to work properly, it needs to pull taut while you are still inside the lifelines to prevent you falling over the side. If it doesn’t do that, one could argue, in the light of MAIB’s Lion report, that you’re safer arming your lifejacket with an AIS beacon and not using a tether at all – at least you could argue that, if getting a crew member back on board was not so unbelievably difficult, even in benign conditions. A PLB will attract rescue services but the situation simply should not be getting to that stage.

I’m almost overboard and the 1.8m tether is still uselessly slack

Another problem is that jackstays are rigged too far outboard. If you take one thing and one thing only from this article, let it be this: rigged along the sidedecks, as they are on most cruisers, jackstays aren’t safe. They are too close to the lifelines and that means you can be pitched overboard. The weather may be bad, it may be dark, the boat may take an unexpected lurch on a lumpy sea, and you’re over the side, be it windward or leeward. That’s all it takes.

To stop being washed aft, Volvo Ocean Race boats sewed loops onto jackstays and clipped onto those

Another drawback of the jackstay as we know it is that there is nothing holding you in place. If you are working at the mast, say, using both hands to put in a reef, and a wave crashes over the windward side, you could have your feet swept from under you and find yourself washed down the deck and out of the scuppers. The Volvo Ocean Race boats suffered a similar problem, in that crew could be washed down the deck and smashed into deck gear. Indeed several injuries were inflicted in this way.

Lateral thinking

Their solution was to sew loops onto the jackstay at the point where crew would be working. They emerge clipped on, head to their station, then clip onto the loop. If a wave swept the deck, they would be pulled up within the length of their tether rather than the length of the jackstay.

One final point, obvious but often overlooked, is grip. Many MOBs result from lost footing. You need to make sure that, when you plant your feet on the deck, they stay put while you work. The deck will be wet, it will be lurching but, as long as you don’t slip, you stand a decent chance of keeping your balance and staying on deck.

What’s the best way to rig jackstays?

A weak anchor point renders your jackstay worthless. Use chunky shackles and properly installed deck strongpoints for jackstay terminals

We have looked at rigging jackstays in many previous articles. Terminals must be proper strongpoints, through-bolted with backing plates, deck cleats or shackles of a decent size on the toerail. The jackstay is only as strong as the fastening.

Dyneema is OK but make sure it’s at least 5mm (breaking strain 1.9 tonnes), bearing in mind that a webbing tether has a safe working load of at least two tonnes. Either buy or make Dyneema soft shackles, or use several loops and plenty of half hitches to secure the tether to the strong point. Don’t forget that, when you leave your boat, webbing jackstays need to be stowed below, out of the sun. This may lead you to conclude that, unless you have soft shackles, Dyneema is possibly not the most convenient fastening.

Clearly the conventional method of rigging jackstays is less than ideal. We sat down to think about a safer way of rigging jackstays. First we looked at the ‘perfect’ jackstay:

- You must be able to clip onto the jackstay from the cockpit

- The jackstay must run as close to the centreline as possible

- It must run the whole length of the deck

- It must be as tight as possible

The safest orientation we found was one that can be used on yachts with mainsheet arches towards the back of the cockpit. The jackstay would run from the centre of the arch forward to the mast base, with a second jackstay running along the centerline to the bow. Legend Yachts aside, we couldn’t think of any other suitable marque. Some brands, like Malö and more recent Bénéteau Oceanis models, have arches but they are forward in the cockpit. Others, like Ovni and Allures, have arches well aft, but the jackstay would foul the coachroof mainsheeting.

A centreline jackstay works on few boats

Most of us will need a Y-shaped configuration adapted to fit our particular deck setup

This arrangement may suit boats with halyard exits in the mast

With halyard exits at the mast base, this could work

Then we came up with a variety of alternative configurations, all of which boiled down to a Y-shape. The aft terminals are outside the cockpit and run forward, over the running rigging, to a strongpoint at the mast, or cow-hitched around it. This allows crew to move along the side deck using a shorter tether, which will pull up before you’re outside the lifelines.

Using the Y configuration, the short tether stops us inside the lifelines, which is what we need

On the foredeck, another jackstay runs along the centreline from the mast to a strongpoint forward. We have seen an orientation that uses a single jackstay, running forward to the mast then back aft down the other side. The foredeck jackstay is cow-hitched onto it and both are tightened using a Dyneema purchase at the bow. I would prefer three separate jackstays, port aft, starboard aft and foredeck, as this will limit stretch, but you need a good spread of strongpoints.

The foredeck configuration will obviously foul the forehatch emergency exit. Whether this is a risk worth taking is up to you. The foredeck jackstay should have enough slack or elevation to enable a knife-wielding

hand to emerge.

Take time to fine-tune your setup

A static tether at the mast, the grey Dyneema line, keeps you secure while you change from one jackstay to the other

One idea is the static tether: a length of Dyneema cow-hitched to a deck strongpoint, with a quick release snap shackle cow-hitched at the other end. These are long enough to enable you to work while standing, and brace your feet against the deck, but keep you inside the lifelines. Think about where you spent most time working on deck and rig your static tethers there.

While transferring between jackstays at the mast, the static tether, clipped on before you unclip your own tether, makes sure that you stay put. A three- clip tether can also do this job, clipped to both jackstays, forward and aft, but we liked the simplicity and security of the static tether.

A Dyneema loop around the mast also serves to keep you where you need to be while working

Graham Snook adapted the idea and spliced a loop of Dyneema around the mast with a quick release snap shackle cow-hitched on. This allows him to use one strop to work on both sides of the mast. However, Pixie’s halyards exit at the mast base. If there were exits higher up, the Dyneema loop would need to be rigged outside the mast’s running rigging to enable you to move around the mast.

Safety on the foredeck

The foredeck narrows toward the bow, bringing you closer and closer to the toerail as you move forward. Even with the shortest safety line, like a 1m (3ft) tether doubled to keep you within 0.5m (18in) of the jackstay, you could still end up over the side while working at the bow.

A Prusik knot attached to your harness can be slid up and down a vertical line but locks onto the line if you slip

YM reader Tony Hughes suggested clipping to a vertical line, like a spinnaker halyard or pole uphaul, instead of jackstays. A fall arrester or a Prusik knot clipped onto your harness is used to slide up and down the vertical line to ensure you’re securely attached at the same level above deck as you move forward. If crew went over the side, a line is already attached and they can be winched back aboard. I had instant visions of being towed through the sea with the boat heeled well over but we decided to try it out anyway.

Combined with a shorter tether on a centreline foredeck jackstay, the vertical line does add security

In early discussions with James and Ash from Spinlock, it was pointed out that, unless the Prusik knot is regularly moved down as you move forward, the vertical line may support your weight on the foredeck, reducing your grip on deck. The boat may lurch and you could lose your footing and swing outside the lifelines.

In practice, I found it worked very well, but only when combined with a tether attached to the centreline jackstay. This has all the benefits of the vertical line but keeps you inside the lifelines. Spinlock’s Ash Holmes, a former sailing instructor, reminded us of the convention that you should never secure yourself to the mast as, in the event of a dismasting, you could find yourself in all sorts of trouble. It’s up to you to decide whether this risk is acceptable.

Are there other ways we can help ourselves stay on board?

While moving around on deck, try to keep both hands free and make use of handholds

I met Steve White in Les Sables d’Olonne before the start of the 2008-09 Vendee Globe. As he talked me through his IMOCA 60 Toe in the Water, he mentioned a comment by a French colleague: ‘He scuffed his boots along the deck and said “Zis deck, it will kill you!”’ Happily it didn’t, as Steve addressed the issue, but it does illustrate how crucial good grip is. If you’re not prepared to repaint the deck, consider grip strips in crucial places where you would expect to spend time working with both hands.

The same goes for footwear. However attached you are to that manky pair of deck shoes or sea boots, have a good look at the sole and decide if you would trust it with your life. Think outside the box. When he was teaching, Ash from Spinlock wore tennis shoes.

Modern boats lack toerails so there’s not a huge amount to brace your feet against. Grip strips here would help a little

Handholds and footholds are also very important, particularly when entering and leaving the cockpit. A bar around the sprayhood is very useful, likewise grip strips on the coaming. Modern boats seem to be clearing the sidedecks, which looks clean but does cut down available footholds. They’re also moulding hull-deck joints rather than bolting through a toerail, which isn’t good for bracing against.

Another feature fast fading into memory is netting on the foredeck lifelines. Cruisers will rarely have a changed sail bungeed to the foredeck these days but netting does provide security if you were to get sluiced to leeward by a wave while working on deck. Christopher Reddish may have received little more than a dousing and a salty story to recount had Lion been fitted with stout Dyneema netting on the foredeck lifelines instead of the bungee twine that served only to keep sails on deck.

A wider gate and a simple unlocking mechanism make this clip easier to use but just as secure

I sailed aboard the Prima 38 Mostly Harmless in the 2006 non-stop Round Britain and Ireland Race. We got round in 13½ days, of which, bizarrely, 12 were upwind. On the stand-by watch, we were usually clipped on at the weather rail. Whether it was fatigue, dehydration, cold or gloves, I often found it frustratingly difficult to open my tether clip, and when I did the little hook on the inside of the clip would snag the tether. Spinlock’s James brought along a larger clip sourced from a mountaineering outlet that uses palm pressure to open the lock, has no hook to snag the tether, and a wider gate. This would be easier to use if you decided to have your own tether made up.

Finally you need a last line of defence: a knife. You may need to cut your tether if somehow you did end up overboard and faced drowning, or to cut your static tether at the helm if the boat inverted. If you were using the vertical line method on the foredeck, you would need to cut yourself free from the pole uphaul if the boat was dismasted.

Fit padeyes in critical places

Deck safety relies on having well-fitted strongpoints in the right places

You need padeye strongpoints just outside the companionway so you can clip on while below, at the wheel or tiller so you can stay on board in a knockdown, and at the mast to secure jackstays and static tethers. They’re not easy to fit on cored decks so consider calling in a pro to ensure absolute security.

Other behaviours that help you stay safely on board

A static tether with a quick release clip at the helm keeps you onboard

As skipper, you should think hard about safety when jackstays, harnesses and tethers are required. Are there enough cockpit strongpoints? Are they in the right place? If you were knocked down, is your tether too long to keep you in the cockpit? Would a short static tether serve that purpose better?

Think hard too about any situation that requires you or your crew to leave the cockpit in rough weather. Can you clip onto the jackstay while still in the cockpit? Are there handholds to help you out of the cockpit, and move forward, safely? Would grip strips help your crew work securely at the mast? What tools do you need, so that you can make sure the trip forward isn’t complicated by a trip back to pick up a head torch or a forgotten tool, or sending someone else forward with the missing kit?

One more thing: if it’s rough, chaps, don’t dangle off the backstay or head for the leeward shrouds to have a pee. Either go below, which involves a fairly tedious amount of undressing, bucket and chuck it, or pee in the cockpit drains.

Deputy skipper

You and your co-skipper need to devise, test and refine a method of retrieving a real MOB. It tends to focus the mind on staying onboard

We can’t get away from the fact that people will go over the side so it’s worth briefly addressing the worst-case scenario here. The truth is that very few of us will practice our MOB drill this summer, never mind with a real person in the water, regardless of how important we know it to be. That means we don’t know how difficult it is first to locate, then to recover an MOB. Perhaps if we did we might take it more seriously.

It took Lion’s crew of seven experienced racers 16 minutes to get Christopher Reddish back on board. The MAIB report concluded that the recovery was complicated, among other things, by the fact that not everyone was familiar with the MOB retrieval drill. Nor did they know that their chosen retrieval method wouldn’t be able to lift the skipper high enough to get him over the top lifeline. The final contributory factor was that there was no co-skipper appointed, so communication became confused and things took longer than they should.

You can spend as long as you like thinking through scenarios, devising solutions and finessing ideas, but what happens if you go over the side, leaving just your panicking crew on deck, or knock yourself out leaving your crew to fumble their way through a Mayday while sailing the boat and administering first aid?

Whatever may happen, you need a shared plan. It’s essential that you and your co-skipper both know and understand the plan, and have rehearsed it, because it’s highly unlikely that your plan works. It will need improvement, and you won’t know where to make those improvements until you put the plan into action. When it works perfectly, that gives you both vital confidence in the plan.

Graham Snook: ‘I’m convinced it helps’

‘After seeing it was possible for me or my crew to fall over the side using the short tether on my existing jackstays, I thought it was time to act.

The distance from my existing jack stay attachment point to forward of my babystay and back to the cockpit was 6m in total. I bought a length of Dyneema, allowing 0.5m for a splice in each end, and an extra 2m of line to make soft-shackles.

Splicing loops in the jackstay and making soft shackles took just 30 minutes

The new Dyneema jackstay is soft shackled onto the existing jackstay anchors

The new Dyneema jackstay is soft shackled onto the existing jackstay anchors

Ideally I would have liked to buy 6mm Dyneema, but even 5mm has a breaking strain of over 1.8 tonnes. It cost £14.25 from YouBoat in Gosport and I spent 30 minutes making the shackles and adding locking splices in the end of the jackstays. So for £15 and 30 minutes in sunshine at anchor, I’ve made my boat safer.’

How to stay on deck and avoid MOB

Even clipped on, you can still go over the side. Chris Beeson finds out how a few simple changes can…

MOB in a Pacific hurricane

As skipper of the amateur crew of Uniquely Singapore, Jim Dobie handled MOBs and knockdowns in Force 12 winds during…

How to make sure you’re not an MOB

We read a lot about MOB recovery but little about how to make sure you don't go overboard. Former RYA…

How an 8st crew can recover a 20st MOB

Could a wife save her husband’s life? Yes, but the key is a tried, tested and trusted plan, says Chris…

Testing MOB retrieval and recovery kit

What’s the best kit for MOB retrieval and recovery? Chris Beeson tested a range of pushpit-mounted products to find the…