Exciting advances in textile design are leading to drier, warmer and lighter waterproof clothing. Sam Fortescue explains the benefits, and the science

Not all that long ago the last word in waterproof clothing was sailcloth coated with tar and some stout woollens. With no more protection than that, fishermen, sailors and explorers achieved the most astonishing feats of endurance in cripplingly bad weather conditions. Frankly put, extreme clothing was pretty rubbish.

As late as the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, sailors were still competing in flannel trousers and Guernseys. However, British sailor Keith Musto, who won silver at the games, was soon to upend all that by bringing in modern technical fabrics for the first time.

The company he founded, Musto, is still at the cutting edge today, but there are now a host of competing high-quality manufacturers, from Henri Lloyd to Helly Hansen. And they are all trying to find the same elusive sweet spot where waterproofness, breathability and comfort meet.

Musto famously uses Gore-Tex in its high performance MPX and HPX wet weather gear, as does Canadian brand Mustang Survival. But what does that really mean? Well, Gore-Tex is the ‘secret sauce’ – the vanishingly thin membrane which makes the garment waterproof and breathable.

Sandwiched between the inner mesh and hard-wearing outer layers of a jacket or trousers, it is actually made of polytetrafluoroethylene (aka Teflon or plumber’s tape), which has been stretched so that billions of tiny pores rupture the surface. This leaves the material minutely perforated, or micro-porous. So, when you’re wearing a Gore-Tex jacket, you’re really wearing a very, very fine filter.

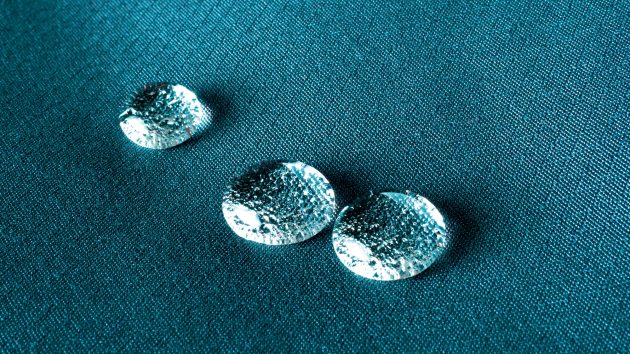

The molecules in liquid water from rain or spray clump together on the outside in groups too big to pass through the tiny holes. In water vapour (on the inside), the molecules are much more energetic, so don’t stick together and can therefore escape readily. This is how perspiration gets out without letting water in, keeping you dry and warm.

Droplets of water can’t penetrate minutely perforated Gore-Tex coatings

‘There is nothing that compares to Gore-Tex,’ says Musto materials manager Suzanne Baxter. ‘The amount of work that goes into the development and the engineering of the product – that ePTFE membrane – is unrivalled. They also adapt their membranes to different end uses.’

Waterproofness & breathability

Water resistance is relatively simple to measure. In essence, you stretch the fabric across the bottom of a tall cylinder, which you slowly fill with water until the fabric begins to leak.

The higher the column, the more resistant the fabric. As the head of water can be 30-40m tall, a machine is often used to generate hydrostatic pressure. Some 1,500mm of water pressure is the legal threshold for waterproofing, but even basic sailing gear starts at around 10,000mm. A really extreme garment can manage 30,000mm or more.

Breathability is harder to measure, and there are several competing tests. One reproduces the column test in reverse, by stretching the fabric over a jar of water or brine and seeing how many grams of it pass through in 24 hours. A good reading would be 10,000g per square metre, then the higher the better.

LEFT: Different brands are now developing their own new waterproof technologies

The other technique is to put the fabric above a perforated metal plate kept at a constant temperature. Water is channelled onto the plate and evaporates through the fabric. Evaporation causes heat loss on the plate, and the energy required to top it up again is carefully measured. The greater the heat loss, the more breathable the fabric. This is expressed as a resistance to evaporative heat loss (RET), where a lower figure is better. Look for 10 or less.

However, Devan la Brash of Gore-Tex’s manufacturer, Gore advises caution with these figures: ‘There are several different tests for both breathability and waterproofness, with different results and units used. It’s like comparing apples to oranges unless you know what test method is used. Having a figure on how a laminate breathes does not always correlate well with how it feels in a garment when you consider other aspects, such as fit or air gaps.’

Bi-component membranes

Gore has made refinements over the years and Gore-Tex Pro, which is the version that ends up in sailing gear, is now coated with a chemical that repels oil as well as water – lengthening the membrane’s useful life. It is a so-called ‘bi-component’ membrane whose pores are filled with polyurethane (PU), which attracts water inside the membrane and rejects it on the outside. Strictly speaking, this means it is no longer porous.

Sailing gear should have a minimum 10,000mm of water resistance

Different waterproof tech

Other sailing brands have developed high-tech wet weather gear that uses the same principles. Zhik’s new OFS900 also uses a bi-component membrane, while its OFS800 foulies use a membrane from eVent made of PTFE. eVent makes much of the fact that its membrane remains air permeable. In principle, this makes garments more breathable.

Japan’s Toray makes its Dermizax membrane from microporous polyurethane, which it supplies unbranded.

Gill uses a non-branded supplier for the micro-porous membrane in its pinnacle OS1 gear. Among the advantages of this flexibility is the price. The OS1 Ocean jacket costs £545 compared to £775 for Musto’s MPX or £630 for Zhik’s OFS800. Gill calls its three-layer fabric Xplore+.

Article continues below…

Best waterproof jackets and salopettes for offshore sailors

The biggest storm should be water off a duck’s back in these rugged offshore waterproofs. The YM team put six…

New gear: Zhik OFS800 foul weather clothing

Zhik OFS800 is the Aussie brand's new range of high-performance offshore foulies, including a jacket, smock, latex smock and salopettes.

Helly Hansen’s top-spec Aegir line includes a heavier layer of polyurethane, as well as insulation. A PU coating has no pores (holes). Instead, its chemical properties attract water molecules and then hands those molecules through the membrane, swinging from bond to bond like an ape through the trees – until the water molecule has reached the outside.

Some gear only has a PU coating, because it has fantastic waterproofing properties. It stretches more easily and doesn’t require that third inner mesh layer to protect it – unlike ePTFE. That can make for a lighter and more comfortable garment as well, particularly around the joints. Many jackets and trousers described as ‘two-layer’ use this approach, including Musto’s BR2 and BR1, as well as Henri Lloyd’s premium O-Race and Freo ranges.

To improve recyclability, Musto has switched from polyester-face fabrics to nylon

‘We use Japanese coating technology rather than a membrane,’ says Henri Lloyd’s Dan Williams. ‘This is a tried-and-trusted technology that we have used for more than 25 years and helped develop.

It is a multi-layered bi-component micro-porous/hydrophilic combination.’ Or, in other words, one coating attracts water from the inside, while another rejects

it on the outside.

Gill’s lighter weight OS2 and OS3 lines use its second-tier Xplore fabric, which combines a layer of nylon with a polyurethane inner coating. This offers other advantages, because the PU layer can be partly bio-sourced, as is the case with the OS2 gear. ‘The bio membrane consists of 50 per cent plant-based glucose and 50 per cent crude oil,’ says a Gill spokesperson. ‘By using a plant-based bio-PU we are able to reduce greenhouse emissions by 40 per cent in its manufacture.’

Recyclability

Recycling is a growing issue in wet weather gear, where polyester and nylon are the most common yarns in use. Both of these can be ‘spun’ from recycled plastic – usually old drinks bottles – and some manufacturers are even experimenting with closed loop recycling, where old fabric is used to generate new yarn.

For Musto, recyclability has meant a switch from polyester-face fabrics to nylon, which has mixed benefits. On the one hand, nylon is finer and can be more densely woven (high denier), helping to resist water. On the other, polyester naturally absorbs water less readily than nylon. Both are available as recycled yarn.

Pip Hare wearing Helly Hansen wet weather gear

All the major brands are involved. Henri Lloyd has been proactive in using recycled yarns for its offshore products, and offers UK customers the opportunity to return clothing they no longer want for a second life with Worn by Us. You can keep 40 per cent of the resale price or, if the garment is unusable, it is recycled. Helly Hansen and Gill also use recycled yarn.

Future waterproof clothing fabrics

Clothing manufacturers are also experimenting with a recycled waterproof membrane, because PTFE uses so-called ‘forever chemicals’. eVent and Toray have both developed membranes that are partly sourced from plant products, such as castor beans.

But Zhik is more cautious about the benefits for sailors. Head of design and production, Drue Kerr, explains: ‘In our opinion, truly sustainable performance waterproof membranes that are suitable for extreme saltwater environments are not yet available. We are seeing the use of alternative membranes and single material products, but they

do not perform in a saltwater environment and tend to degrade very quickly.’

The words ‘saltwater environment’ really are key here – lots of developments from other sectors sink on the high seas. But there is hope. Amphitex, for instance, has been spun out of a university project to use new yarn and membrane materials to eliminate PTFE and PFCs.

Gore is currently testing a PTFE-free membrane with Musto in The Ocean Race, based on expanded polyethylene (ePE). It has performed well in other sectors, and is already available in sports and outdoor wear. ‘We’re confident that the new Gore-Tex membrane will be suitable for water application,’ says Gore’s Devan la Brash. ‘Extensive field testing to date shows positive experiences for the wearers and final conclusions will be made in the coming months.’

And then there’s Allied’s idea of nano coating natural down with gold, to dramatically increase the rate at which water evaporates.

Polartec, meanwhile, is using an entirely different process for creating microporous membranes using polyurethane, which could have benefits for sailors in time. It uses a novel technique called ‘electrospinning’, which gives much closer control over the structure of the membrane. Branded Neoshell, the product is extremely breathable, but less waterproof than Gore-Tex. However, it does have huge potential.

Companies are focusing hard on finding alternatives to environmentally harmful water repellent chemicals

Environmental concerns

Whatever the fabric or membrane type used, there is one aspect that every piece of waterproof sailing gear has in common – the exterior is treated with a Durable Water Repellent (DWR) chemical, designed to reduce the surface tension of the fabric, so that water beads and rolls off, instead of wetting out.

Unfortunately, the compounds that achieve this best are hazardous. So-called ‘forever chemicals’ or PFCs don’t break down in the environment – which is why they work so well when the sea is throwing everything at you. There is also some evidence to show they cause cancer and reduce fertility. They have also now been found in the most pristine and remote environments on Earth, from the Amazonian rainforests to the Antarctic.

Clamping down on chemicals

The EU is mulling a timetable for phasing these chemicals out of clothing by 2027, while California is aiming for 2025. Ocean racing is exempt, but not leisure cruising, so the industry is rushing to develop sustainable alternatives. The first step has been to move from long-chain C8 chemistry to short-chain C6. ‘C8 is still allowed in heavy industrial wear, police gear and so on, because it gives the best wear,’ explains Musto’s Suzanne Baxter.

‘Then we went down to C6 tech, so the product breaks down in the environment easier. We did a big trial with the GB Sailing Team coaches – they put ridiculous hours on their kit, took it offshore, and they didn’t see much of a difference.’

Musto’s HPX Gore-Tex Pro Ocean Drysuit has been tested in the toughest offshore conditions

Musto has formulated a PFC-free treatment, which it uses in its BR2 line. ‘We’ve added more into the mechanical finish but one of the problems when you do that is it reduces the breathability,’ continues Baxter. ‘We changed the membrane to make it more breathable to counteract the extra chemistry we had to put into the fabric. We moved to a bi-component membrane with hydrophilic membrane on the inside.”

Henri Lloyd is also researching its own solution. ‘There are exciting developments that we are testing which don’t rely on PFCs – once proven we will introduce them,’ says Dan Williams.

Zhik, meanwhile, has already formulated a new ‘green’ DWR treatment, which it markets as XWR. It is super stretchy and appears on some of its lighter-weight tops at the moment. ‘It is currently not on our range of OFS (offshore) gear, but as those ranges get refreshed and made in future, all the lines will be moved to the PFC-free coatings,’ explains Drue Kerr.

Gill uses recycled yarn in its garments

Plant-based coatings

The consensus is that green DWR is less effective than PFC, but Gill claims it has managed to square the circle with XPEL, now used on all its wet weather gear. ‘We believe we’re the only marine brand to offer this level of water-repellency through a plant-based DWR coating,’ says a spokesperson. Louis Burton and Conrad Colman have tested the finish in the Southern Ocean and on the Route de Rhum.

Beyond sailing, a host of manufacturers are formulating new so-called ‘C0’ DWRs from Archroma’s Smart repel Hydro to Fjällraven’s polyurethane spray. Musto is looking into the possibility of using more hydrophobic polypropylene yarn, as well as infusing the yarn itself with a water-hating treatment.

Enjoyed reading this?

A subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

YM is packed with information to help you get the most from your time on the water.

-

-

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our experts

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment

- Cruising guides to help you reach those dream destinations

-

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.