When Mike Goodwin and his crew spotted something in the water at the end of their charter, they were unaware of the life and death drama in which they were about to play a part. This is his harrowing account of what happened

Under reefed mainsail and engine we were heading westwards, close to the rocky cliffs off the French south coast, east of Marseille. In the distance I saw something in the water – some colours, I wasn’t sure what, exactly.

I was skippering and helming our charter boat, Naima, a 45ft Dufour, as we made our way back to the charter base at Marseille. Also on board were my wife Diane, our friends Rob and Madeline, my son Cliff and his partner Ash.

Weather breaks

It was September 2018 and we were reaching the end of a marvelous week of sunshine sailing. Now, on the final day of our charter, the weather had broken and a strong Force 6 from the west slowed our progress, picking up uncomfortable seas as it blew against the west-going tide.

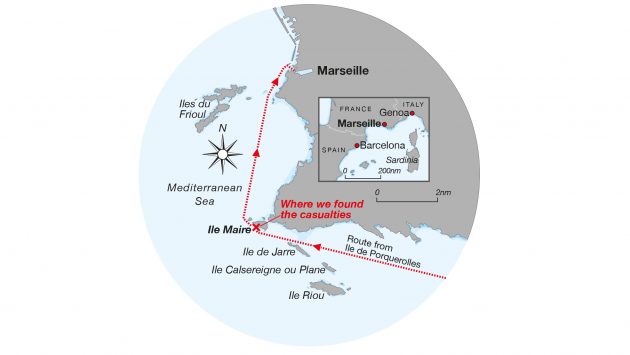

The beauty of France’s calanques and rocky coastline – yellows, greys and browns – lay to starboard. Ahead lay Île Maïre which we would leave to starboard, and beyond that was Marseille.

Charter boat, Naima, a 45ft Dufour, with the bathing platform at the stern lowered

I glanced away momentarily. When I looked back, whatever I had seen had disappeared. It was just some jetsam perhaps. Anyway, it was now hidden by waves which were building up to 3 metres. My attention returned to helming Naima. Conditions were demanding but we were coping well.

Some minutes later, as we drew alongside Île Maïre, Ash spotted them. ‘There are people in the water over there!’ he exclaimed, pointing towards the cliffs. Sure enough there were three people very close to the cliffs, and they were desperately fighting for their lives. Hoping there was another boat on the scene that could save them, I looked around for it. There wasn’t one. It was going to have to be us.

Do we get the mainsail down or attempt a recovery with the sail set? I decided on the latter. We didn’t know how long the casualties had been in the water, and time might be of the essence. Even in September the sea is very cold. We sheeted in the mainsail tightly, then I swung Naima around to travel downwind to enable an up-wind approach to the people.

We lowered Naima’s bathing platform, and rigged a line from the stern for throwing. Ash asked whether we should press the emergency distress button on the VHF radio. I told him to do so.

Rocks danger

As we made our approach I was very conscious of the cliffs and the possibility of the wind or waves pushing Naima’s bow to starboard. If that happened the mainsail would fill and power Naima into the rocks. We needed to maintain some movement to have steerage, or at least we needed to stop only momentarily.

As we made our approach Rob stood by with the rope before throwing it to the people. They were unable to grab it, and I had to power Naima away to keep us off the rocks. We repeated the operation. On the third approach the lady in the water managed to grab the rope. With the help of Rob and Ash she climbed onto Naima’s bathing platform.

We had to power away again immediately to stay off the rocks. We made a further approach for the other two men. It was obvious by now that the older of the two was unconscious and grey. My immediate thought was that he was dead. Even so, the younger man was holding his head out of the water in an attempt to save him.

Cliff helming as Naima sails past the rocky shore, before they spotted the MOB

Prank call

Meanwhile Cliff was following up our distress signal with a voice call over the VHF radio, but got no answer. He tried telephoning 112, the international emergency number, and spoke to someone who claimed that the location coordinates Cliff gave, taken from our chartplotter, represented a point on land!

I told him to say that we were south of Île Maïre. The person on the phone hung up. Did they think it was a prank call? Cliff rang again and spoke to someone else, having to explain the situation again, shouting desperately, ‘Two casualties in the water, one unconscious, please don’t hang up. Don’t hang up!’

We made further circuits attempting a recovery of the two men. The rescued lady thought initially that we were leaving them. She started to cry and almost threw herself back into the water to help them. Diane yelled at her to sit down. Ash fetched her a blanket and Madeline gave her a drink.

The lady told us her name was Valerie, and the two men were her husband, Jean-Pierre, and son Davide. She and Davide had arranged the day out as a birthday gift for her husband, hiring a small motorboat so that they could go to photograph the rock formations.

In and around the calanques were many small open sportsboats like this one, usually chartered for day trips

Their boat had been swamped by waves and had sunk quickly, leaving them no time to put on their lifejackets. They had been in the water for an hour. Two boats had already sailed past and not noticed them. Valerie had been ready to give up but Davide kept telling her to hang on. She had prayed very hard that they would be rescued.

We made further circuits to pick up Davide and Jean-Pierre, all unsuccessful. It was too difficult to stop Naima and keep her off the rocks and off the casualties. On one pass I lost sight of the casualties and Rob yelled that they were almost under the boat. Even when we were close it was difficult to throw the line to them, and Davide was using his own arms to keep himself and his father afloat. He was probably very cold and had little strength left. It was impossible for him to grab a rope as well, let alone pull himself on board Naima.

Second yacht

We stood off a while and took down the mainsail in the hope that we would have more ability to manoeuvre. Another yacht, Cristar, appeared on the scene and attempted to rescue the men. We could not continue our rescue attempt for fear of colliding with Cristar. There were two crew and they were also unsuccessful in their attempts to recover the men.

Finally, at last, a French SNSM lifeboat (equivalent to Britain’s RNLI) appeared. Two crew jumped into the sea and plucked the casualties out with them, with the help of a crane on the lifeboat. The lifeboat then zoomed off to its base.

We took Valerie back to Marseille. Diane and Madeline walked her to the capitainerie – the harbour master’s office. Eventually an ambulance came to take her to the hospital where Davide and Jean-Pierre had been taken. We learned later that Jean-Pierre had died.

ABOVE: The area where Mike and his crew found the casualties – the coastline around Marseille is typically rocky and inhospitable except in the bays and limestone coves known as calanques

Lessons learned

Keep a lookout – I should not have assumed it was jetsam in the water. We could have begun the rescue a few minutes earlier if I had looked through binoculars.

Communication back-ups – Don’t assume there will be a response to a VHF radio call. Have a back-up plan.

Plot your position – Always know your position accurately. The person Cliff spoke to was convinced he was describing a point on land. Perhaps because we were very close to the land? Eventually he spoke with someone who said they could ‘see’ our distress signal location.

Throwing lines – Throwing the line accurately was a challenge. It may have been helpful to have had a longer line with a bowline on the end, and with a fender tied to it.

Wear a lifejacket – I always ask my crew to wear a lifejacket, even if it seems unnecessary. Conditions can change very rapidly and by then you may be too busy managing the situation. Jean-Pierre would have had a much better chance of survival had he been wearing a lifejacket.

Give a safety briefing – The safety briefing I gave on boarding was invaluable – Ash knew about the distress button on the VHF radio.

Getting casualties aboard – The biggest problem was getting the casualties on board. If the men had been able to help themselves then I’m sure we would have got all three on board. Had the SNSM boat not appeared I might have attempted recovery of the unconscious man by winching him aboard using the topping lift.

Our method worked for Valerie – had one casualty not been unconscious I’m sure it would have worked for the others, but it would have been good to have had a means of getting unresponsive casualties on board too.

Enjoyed reading this?

A subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

YM is packed with information to help you get the most from your time on the water.

-

-

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our experts

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment

- Cruising guides to help you reach those dream destinations

-

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.