Yachting Monthly editor, Theo Stocker speaks to three modern wooden boat manufacturers to find how this old material has remained at the forefront of technology

‘Building a wooden boat, you don’t need a new plug and mould for every boat you want to build, so there is much lower setup cost, and less waste,’ says Spirit Yachts’ Adrian Gooderham. ‘A large part of the cost is in the skilled labour.

‘First, we make a strong back on which to build the boat. This is in pine, and that timber will be used multiple times in the build of that or other boats. Eventually, it will be too small to use again, and we then either donate the wood, or our staff use it as firewood.

‘Spirit yachts are built with plank-on-frame in either yellow cedar or Douglas fir, and are then strengthened with two opposing diagonal veneers of 3.2mm thick khaya laminated in place. This is then sheathed with two layers of 450g/m2 epoxy fibreglass and a final finishing twill on the topsides. This stabilises the boat and ensures a solid base for fairing and painting.

A pine strongback is built, to which frames are added and braced. Photo: Spirit Yachts/Mike Bowden

‘We recently built two of our Spirit 30 dayboats using bio-resins and flax fibre. Because these are natural products we were happy to use them in place of the khaya veneers, with four layers of flax providing the strengthening on top of the strip planking. We used West’s Pro-set bio-resin for this and it is more than strong and stable enough to build boats that meet our standards.

Article continues below…

Are wooden boat the answer to environmentally responsible yachting?

Boatbuilding as we know it is not a sustainable process. The dawn of mass production GRP boats from the 1960s…

Teak wood: why the popular wood’s time is up

Choosing the most sustainable options for your boat can leave you feeling confused, but don’t worry, you’re in good company.…

‘The downside for us with this is that it needs to be post-cured at 25ºC for two weeks, where 105 epoxy self-cures at ambient temperature. In order to build larger boats with these bio materials, we would need to look in depth at whether the additional energy costs of post curing and the means of doing this are worth it – we can’t just put a wooden boat in an oven as you can with a GRP boat.’

The hull is then strip-planked before receiving two diagonal veneer layers. Photo: Spirit Yachts/Mike Bowden

RM Yachts

‘For the structure of the sailboat, we use high-end Okoumé plywood of 15, 18 or 22mm depending on the boat model,’ explained Dohy. ‘All wood cuts are made digitally by our subcontractor. The panels arrive at the RM Yachts yard ready to be assembled and glued on a jig, at the same time integrating the steel structure which will support the keel and mast.

‘Just before “unmoulding” a first inspection is completed of the fillet joints between the partitions. Each bulkhead is structural, laminated to the hull. While still upside down, the chines and connecting laminations are coated with epoxy filler and a first sanding is done.

The hull is then turned over with the help of a crane, and this layering work continues, this time upright. Note that each plywood part is epoxy coated, for optimal sealing and increased rigidity.

‘The entire interior of the boat is then primed and painted white. Bundles are passed for electrics, plumbing, water and diesel tanks, motors and peripherals such as batteries. Then, depending on the model, some of the joinery is fitted before the deck is attached.

Each model has a jig that can be reused multiple times, onto which are laid the plywood hull panels. These are then laminated in place before the hull is turned over and the interior joinery fitted. PHoto: RM Yachts

‘On delivery of the deck (made by a subcontractor, in PVC foam sandwich, polyester glass fabric using vacuum infusion) all the counter-moulding in plywood is made up inside. The deck is epoxied in place and over laminated to form a single structure, completely leak-free and with no visible join.

‘Then, with a spray gun, a very thick primer paint is applied to fill in any differences in levels.

‘A second coat of thinner epoxy primer is then applied. This “finishing” epoxy stretches better, and improves the surface condition before a second sanding is done.

‘Then finally comes an ultra smooth polyurethane primer. It is the latter that will receive the final bi-component polyurethane lacquer, which is shiny and, unlike gelcoat, can be personalised to any colour the customer wants. And finally, the deck fittings, systems, keel, rudders and masts are all added.’

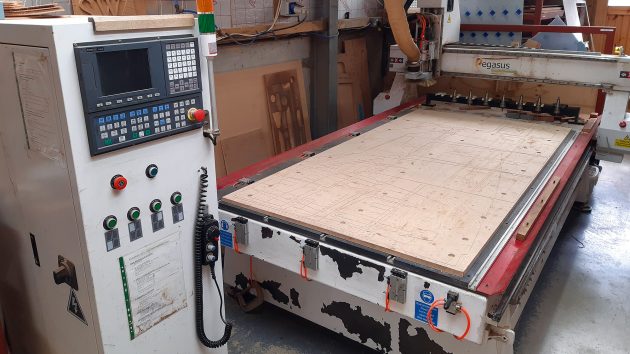

A CNC machine ensures every cut and hole is done with complete precision and a minimum of waste. Photo: Swallow Yachts

Swallow Yachts

‘Wood construction has traditionally been more expensive, with more maintenance for the end user,’ says Matt Newland. ‘Modern advances in CAD CAM technology, and in surface treatments like epoxies and two-pack paints, render both of these arguments obsolete for modern wood construction.

‘Swallow Yachts design its wood epoxy boats so that over 95% of the basic structure is cut using computer-controlled milling machines. These not only cut the shape of the piece, but also holes for hinges, latches, catches and pipework.

If this stage is thought through properly, it saves a huge amount of time on the fit out and brings the costs for series-built boats much closer to GRP ones, especially when the mould cost is taken out (wooden boats need to be built on a strong frame, but this is a fraction of the cost of a full mould which is needed for GRP boats).

The resulting hull is as stiff as a GRP alternative at a much lighter weight. Photo: Graham Snook

‘We build an upside-down frame on a steel strongback. CNC panels are laid on top and laminated to it to form the lower part of the hull. This is then glassed, cured, faired, painted and even antifouled before the hull is turned over. Turning over is much easier to do at this point while the boat is nice and light, and as turning over is also expensive in terms of time, we do it only once. With the boat the right way up, we then add topsides, interiors and decks once the other way up.

‘At the moment, our CNC machine has to be loaded with each sheet by hand for “printing” but we’d like to invest in a loader so that multiple sheets can be cut without additional input. Boats are never going to be built in the volumes that cars are, so the investment for full automation of processes is never going to be economical.

However, we did come close to buying a robot that could go up and down fairing and sanding the hull, which takes a lot of time to do by hand, but at the moment the cost is just a bit too high.’

Enjoyed reading this?

A subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

YM is packed with information to help you get the most from your time on the water.

-

-

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our experts

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment

- Cruising guides to help you reach those dream destinations

-

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.