Each month Yachting Monthly's resident expert, James Stevens answers a reader's question. This month should this reader make a difficult harbour entrance?

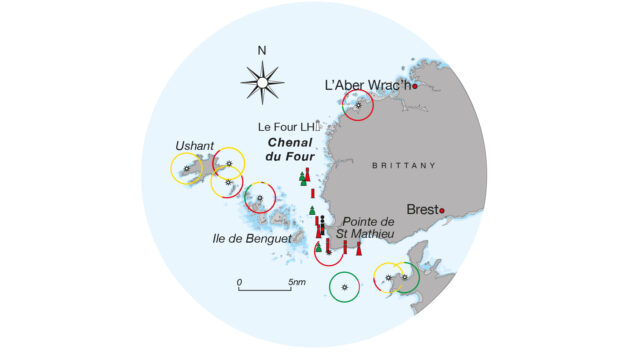

Dave and three friends are sailing their 10m cruising yacht from the Solent to Brest. They were going to enter L’Aber Wrac’h, a rocky inlet in north-west France, for the night, but the tidal stream is favourable for the passage South through the Chenal du Four and on to Brest.

The wind is a light easterly, and they are just approaching Le Four lighthouse. They are hoping to pass through the channel before dusk arrives in about two hours.

Dave is navigating by using a detailed paper chart and an old chartplotter, which he knows occasionally fails and gives a blank screen. He is hoping it will keep working for long enough to pass through the Chenal du Four where the tidal streams are between three and five knots. He is looking anxiously at the weather, the visibility is dropping and it looks like fog ahead.

The channel has rocks on either side and is well marked by buoys. As they approach the buoyed channel, the plotter screen goes blank and no amount of button-pressing and cursing gets the electronic chart back.

There is no other electronic means of knowing the yacht’s position except the VHF radio which gives latitude and longitude figures. Visibility has dropped to about half a mile and the tidal stream is now running south at about three knots.

The crew, who have sailed over 200 miles non-stop, would like to arrive in port. What would you do?

Should you enter this harbour with a navigation electronics malfunction?

The simplest answer is to sail north slowly against the tidal stream into clear water, not too far because there will be shipping further north. Positions from the radio can be plotted on the paper chart. It might be possible to reach L’Aber Wrac’h, but it could be a challenging entrance in the strong foul tides.

The other option is to attempt the Chenal du Four, but it requires some preparation. While Dave is working it out, the best plan is to head into the tidal stream and sail or motor slowly to stay more or less stationary over the ground.

The yacht is safe as long as Dave knows its position on the chart, so his problem is to transfer the numerical readout on the radio to a position on the chart quickly.

The easiest way to do this is to draw a lattice of lines of latitude and longitude on the paper chart along the route, marking each one for easy reference. Some of these can show the limits the yacht must stay inside. It becomes a paper version of cross track distance.

Dave can plot the position regularly on the chart and continually check whether the yacht is staying in safe water. The crew need to be on deck with binoculars, keeping a careful lookout for buoys and other vessels.

Navigating this way is hard work, but before GPS, yacht skippers still managed to find their way through fog and strong tidal streams.

Enjoyed reading this?

A subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price, so you can save money compared to buying single issues.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

YM is packed with information to help you get the most from your time on the water.

-

-

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our experts

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment

- Cruising guides to help you reach those dream destinations

-

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Note: We may earn a commission when you buy through links on our site, at no extra cost to you. This doesn’t affect our editorial independence.