Alastair Buchan and other expert ocean cruisers explain how best to prepare when you’ve been ‘caught out’ and end up heavy weather sailing

Heavy weather sailing

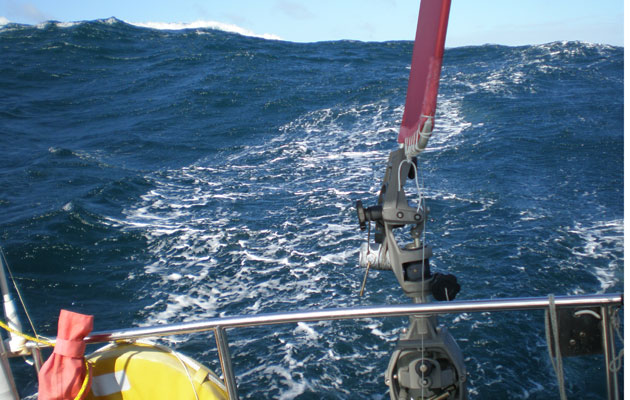

Prolonged heavy weather at sea generates fear and uncertainty, saps morale and leads to poor decision making.

But it doesn’t need to.

As Roger Taylor, a highly regarded ocean sailor and author, points out, this is when preparing the boat properly and having a clear, well thought-out strategy allows you to see the storm not as an ordeal demanding superhuman strength, skill and endurance, but as just a different type of weather.

Well-found and strongly-crewed yachts survive most weather unscathed.

Are we likely to find ourselves at sea in a storm?

Probably not. Accurate forecasts are readily available these days so there’s less likelihood of finding yourself out of reach of land with bad weather closing in, but still it happens.

Perhaps it’s the temptation to sail on a marginal forecast to make sure you’re home for work on Monday.

Maybe on longer passages, crossing the North Sea or the Bay of Biscay, after three or four days at sea the latest weather forecast can warn of storms undreamt of when you sailed.

It could be that the forecast is just plain wrong. More likely still, a combination of the above.

It’s not always a good idea to run for shelter as onshore gales can shut every harbour within reach – the Portuguese coast is a good example.

On the Dutch, German and Danish North Sea coasts, the ten-metre contour is around five miles offshore – a surfer’s paradise.

The Scheldt, Ems and Elbe estuaries are dangerous and the Seegats between the islands impassable.

My 1975 edition of the DHI’s Nordsee-Handbuch warns that in stormy weather small ships should not enter or leave the Elbe as they will suffer Strandung und Totalverlust or ‘stranding and total loss’.

We spoke to several shorthanded or solo offshore sailors with experience of weathering storms in waters most of us avoid.

Their advice is hard-won and extremely valuable, but those of us who sail in home waters may not have the same priorities.

In the middle of the Atlantic, losing 100 miles of sea room is inconvenient but unimportant.

In the Channel or the North Sea, it could be disastrous.

This lack of time and space means that, if we are to cope comfortably, our preparation must be better, and execution smoother.

We’ve broken the advice down into four sections; three for those who find themselves in heavy weather, and the fourth looks at modifications our experts have made to their boats.

Continues below…

We Tested 2025’s Best Inflatable Lifejacket and PFD’s for Boating and Sailing

We all have lifejackets on board, but do you know what yours is actually like to use? We test 10…

From offshore sunset cruising to ocean survival in the Atlantic

A beautiful Atlantic cruise turns into a heavy weather situation for Maarten Zeeuwen

Erik Aanderaa: Viking of the high seas

Katy Stickland talks to Norwegian sailor Erik Aanderaa about why he searches out the worst weather the North Sea can…

Lessons learned from abandoning ship mid Atlantic

Solo skipper Billy Brannan lost his home when his 34ft yacht Helena was knocked down, rolled and dismasted during an…

Our expert panel of seasoned heavy weather sailors

Alastair Buchan

During two Atlantic circuits, Alastair Buchan weathered an eleven-day gale with winds rarely below 45 knots, a three-day Gulf Stream storm and played dodgeball with 135-knot Hurricane Lenny

The oldest woman to sail solo and non-stop around the world, on her third attempt, aboard her Najad 380, Nereida. Jeanne has survived knockdowns, rig failures and worse

An ex-Royal Marine who has sailed thousands of miles in Arctic and Antarctic waters, and sailed through the Northwest Passage in both directions in his 33ft Westerly Discus, Dodo’s Delight.

A solo sailor and author with a passion for high-latitude ocean voyaging, most famously aboard his 20ft junk-rigged Corribee Mingming and now in Mingming II, a junk-rigged Achilles 24

An ex-Royal Marine and ocean sailing legend, whose exploits in his gaff cutter Black Velvet have won awards for adventurous voyaging from the Royal Cruising Club and the Ocean Cruising Club.

Plan and prepare for heavy weather sailing

The message from our experts was clear: prepare well in advance.

Is there any equipment you need, from an EPIRB to an emergency VHF antenna?

Is there anything your boat needs, like stout lee cloths or a bolt lock on the chart table?

A storm jib sets much better on a removable inner stay, can you fit one to your boat?

Do you or your crew need additional training, such as sea survival?

What would you do if the plotter went down?

Does your passage plan identify all dangers such as shipping lanes, headlands with the overfalls, shallow banks with breaking seas, rocks and reefs?

Do you know your position in relation to each hazard?

How strong are the tides, and is it wind against tide?

The sea state in the Bristol Channel can approach that of a full gale in a mere Force 5.

Look for boltholes. On the west coast of Scotland you may find shelter deep in a sea loch.

Once, when fishing boats filled every free space in Mallaig, we hid deep in Loch Nevis.

We spent a few tranquil days while outside the weather went berserk.

The pilot books’ local knowledge is invaluable.

Stay weather aware

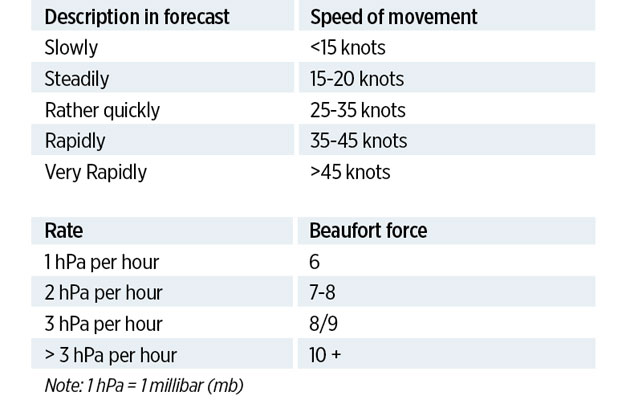

Each forecast states how fast a system is moving, and the barometer’s rate of drop gives you an idea how hard you’ll be hit

There is no excuse for not having the latest forecast, and the sooner you know heavy weather sailing is coming, the longer you have to prepare for it.

Forecasts often give the rate of movement of a pressure system.

Knowing this in knots can help you calculate how long you have before it hits.

It’s important we don’t lose our own forecasting skills either.

Watch the clouds, because cyclonic systems follow a predictable sequence with each step having its own cloud formation, windshifts and weather.

Check the rate of change in air pressure.

For years I logged barometer readings every hour with an arrow to tell me at a glance if the pressure was rising or falling.

The rate of change in a falling barometer gives a good indication of wind strength to come.

On deck preparation

Check everything above deck is ready for the worst before the seas and winds build up.

Jeanne Scorates speaks for all our experts when she advises that ‘there should be nothing on deck to worry about, except a well-strapped down dinghy and liferaft stowed somewhere that’s accessible in any kind of emergency’.

Many believe that is the transom or pushpit. Dinghies on davits are a problem in big seas.

If possible, they are best removed for offshore passages, or lashed down on the foredeck.

If you are towing an inflatable dinghy, bring it aboard, deflate it and stow it securely.

Rig extra lifelines on deck and reduce windage where practical.

Stow securely or lash down all loose ropes, warps and halyards.

Reduce sail well ahead of the storm.

If you are using storm sails hoist them early while working on deck is safe and easy.

‘In strong conditions, I regularly furl the genoa away and sail under reefed staysail and deep-reefed main,’ says Jeanne.

If you plan to stream warps or set a sea anchor make sure everything for this is on deck, secure and ready for deployment.

It’s advisable to disable the wind generator early as it can overheat, and consider heaving-to with storm sails rather than using furling headsails.

These don’t set properly and may unfurl if the clutch gives or the line snaps.

If a furler is your only option, consider lashing the furler or the tack to the pulpit so it can’t unfurl.

On deck checklist

- Lifejacket and harness on

- Rig jackstays

- Clear deck of anything not well secured

- Blank all dorade vents, drop sprayhood, remove dodgers

- Reef deep and early

- Check all rig fittings are secure

- Lash down anchor, or remove and lash below, and secure anchor locker lid

- Make sure cockpit drains are working

- Check cockpit manual bilge pump is working

- Check liferaft lashings and taffrail safety kit are secure and operational

- Prepare any drag devices, sea anchor, drogue, warps etc

- Check cockpit lockers to make sure heavy items are secure, then lock lids

Ewen Southby-Tailyour’s storm briefing

Share your plans with the crew. Make sure everyone knows what’s expected, and what’s expected of them

Once you have decided on your best course of action, Ewen Southby-Tailyour advises: ‘Brief your crew, making sure you cover all eventualities from man overboard to a knockdown or even an inversion, from losing a mast or spar, to serious leaks and fire.

This gives everyone the same picture and it’s an opportunity for crew to seek clarification, ask questions and make suggestions.

The briefing should cover:

- The present weather

- Likely future weather

- Your strategy for dealing with the weather to come

- Revised watchkeeping system including use of AIS and radar

- Allocation of responsibilities, tasks and the timings for carrying them out

- Safety procedures

- Damage control measures

- Communications (ship to ship and ship to shore), including Mayday calls

Below deck preparation

Make sure that everything below decks gets stowed and stays that way.

Paper or clothing can find its way into the bilges and block the strum box (bilge pump strainer).

‘I suffered a knockdown off Cape Horn,’ says Jeanne Socrates.

‘Heavy books flew across the cabin and the chart table opened, throwing its valuable and sharp contents everywhere.’

In the 1998 Sydney Hobart Race, 51 per cent of injuries reported were broken or cracked ribs.

Roger Taylor himself says: ‘I broke ribs during an inversion in the Davis Strait, between Canada and Greenland.’

Ewen Southby-Tailyour advises rigging lifelines below as well as above decks.

Fitting the strong points for this might be part of your pre-sail refit.

If you can, contact someone and let them know your position and plans.

Mark your position on a chart, bring and keep the log up to date and check the barometer regularly.

Is warm clothing in a waterproof bag handy?

Where are the distress flares, or the rigging cutters?

Check the EPIRB and make sure everyone knows how to use it.

Check everyone is properly kitted-up, warm and waterproof.

Make sure everyone eats a hot meal.

If you have time, prepare a big, thick stew in a pressure cooker as hot food is an important morale booster, but make sure the lid is locked and the cooker stowed securely.

Have hot drinks in unbreakable flasks and plenty of snacks to hand.

Below deck checklist

- Take anti-seasickness measures that work for you

- Make a meal or flask of soup, fill pockets with snack packs and put bottles of water in secure places on deck

- Close and lock all hatches

- Clear everything from surfaces and lock all lockers

- Close all seacocks

- Empty bilge and check strum box is clear

- Charge handheld VHF and run engine to charge house batteries for auto bilge pump operation

- Prepare grab bag and move to readily accessible position

Strategic preparation

Ewen Southby-Tailyour recommends a flexible watch system with shorter hours: ‘Self-steering systems can’t ‘see’ sea state, which often means helming by hand throughout.

‘This is tiring, especially at night, and a tired helmsman in a storm is dangerous. Regular breaks are needed.’

Make sure your plan considers your boat, crew, experience and sea room.

Be ready to modify the plan as circumstances change.

You will probably start by heaving-to or sailing under storm canvas.

If the windspeed increases some other tactic such as deploying a sea anchor may be more appropriate.

Most of us meet bad weather without venturing beyond the continental shelf, so our seas are likely to be short and steep.

Upwind progress is slow or non-existent, even if motor-sailing.

Mid-ocean wavelengths will be longer but watch out for cross seas that can throw your boat sideways.

Squalls can easily double windspeed briefly but the torrential rain they often bring can flatten the seas.

Remember too that, when there is a choice of directions to sail, in the northern hemisphere, steering south helps shorten the onslaught.

Heavy weather tactics

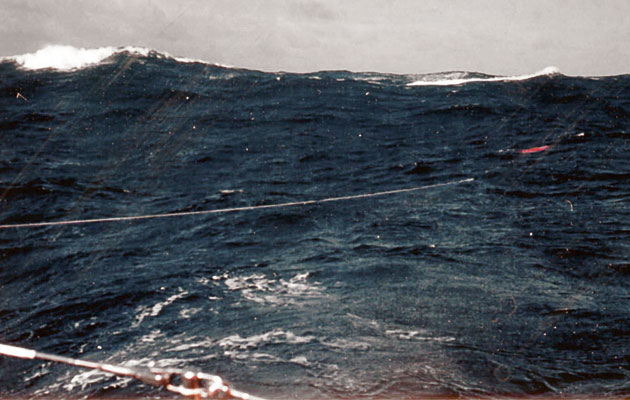

The one golden rule is to avoid breaking waves.

A crest the height of your beam or higher can capsize you.

Smaller ones can fill the cockpit or smash hatches.

Consider tides or currents too, as wind over tide will kick up a steeper sea.

There is no one technique guaranteed to keep you safe so you must choose the best option for the current situation.

We can’t deal with this subject in detail here, but we will look briefly at some coping strategies.

Sail upwind

The 1998 Sydney-Hobart Race report concluded: ‘Yachts that continued to ‘actively sail’ and had sufficient speed and power to negotiate the waves and avoid the breaking crests, generally fared better.’

Three-quarters of the skippers said their boats handled the conditions best when beating, fetching or reaching.

It requires skill, it’s tiring because it demands the helm’s total concentration, it’s frustrating because you will fall off some of the waves with a bang that could pop a bulkhead, and the motion is dangerously uncomfortable.

For shorthanded cruisers, it’s an option if you’re on a lee shore but best avoided otherwise.

Sail downwind

The best angle to take the wave is 15 degrees, as this allows the helm to surf away from breaking crests and avoid pitchpoling.

You need steerage way to position the boat so keep a scrap of headsail up unless you can make enough way under bare poles.

It also demands lots of sea room and your course may take you deeper into the storm or into shipping lanes.

It’s more comfortable and very exhilarating, but tiring because of the concentration involved, so is ill-suited to shorthanded cruising.

Heave to

Bob Shepton has found that it’s nearly always necessary to heave to at some point while on passage in the North Atlantic

We covered this in our August 2014 issue and found that the longer the keel, the better she will heave to.

Gaff-rigged pilot cutters heave to immaculately, but most fin-keel boats heave to poorly in a big sea because there’s nothing below the bow to prevent wind and waves pushing her beam on.

Jeanne Socrates says, ‘My Najad 380’s long fin-keel hove to well under deep-reefed main alone in 30-40 knots winds.’

It’s an excellent tactic but try it beforehand to find the balance of sails and helm position.

Lie a’hull

This involves nothing more than dropping all sail and lashing the helm in such a position that the bow is kept to windward of the beam, then going below and dropping in the washboards.

It can work well provided there are no breaking crests.

Deploy a drag device

A drogue, deployed off the stern limits speed to 3-6 knots, preventing surfing down waves while allowing the boat to steer away from breaking crests

When running off or lying a’hull are too dangerous, you can deploy long warps or a drogue off the stern.

This slows the boat down to 3-6 knots, so you can still steer to avoid breaking crests, without surfing down waves.

Roger Taylor has deployed his Jordan series drogue twice. ‘It immediately defused any threat, keeping the yacht riding easily and elastically, stern-on with little yaw.’

A sea anchor, deployed off the bow, limits drift to under 1 knot – important if sea room is an issue. It needs to be big otherwise the boat will surf backwards down waves and damage her rudder.

The rode needs to be long enough for the sea anchor to be one wavelength away, so if the boat is at a crest, so is the sea anchor. Otherwise the rode will suffer snatch-loading.

Once it’s passed

As the winds begin to drop, Jeanne Socrates recommends establishing where you are first. Note her nav seat lee cloth

Once the weather begins to ease Jeanne Socrates warns not to relax.

Check your position, wind, tides and update your passage plan.

‘This is when you should inform your shore contact of your current position and future intentions, that you’re safe,’ says Ewen Southby-Tailyour.

Next, check all hull fittings, hatches, standing and running rigging, the bilges and bilge pumps.

Check the engine, electrics, battery and fuel state.

Clear up the mess on deck, aloft and below that comes with bad weather.

Dry wet clothing and kit.

Return to normal watch-keeping routines, get proper rest and have a hot meal.

Discuss events with the crew. What worked? What didn’t? What will you do differently next time?

Prepare for heavy weather

How does your boat heave to? Do you have suitable warps for streaming astern, or for a drogue system?

Have you practised deploying and recovering them?

It is not easy even in a flat calm. How long does it take you to bend on storm canvas?

What sail plan is best for your boat?

Ewen Southby-Tailyour recommends: ‘Practice when the going is easy. In a blow, it can be the difference between success and failure.’

Can you use a storm sail as a sea anchor? Is the moment you need it most the right time to find out you can’t?

Do you have a sea anchor?

Caught in a southerly Force 11 off the south coast of Iceland, Ewen tried making one out of a storm jib but conditions were so bad, he was unable to get the three rigging lines to the correct length.

Once it was deployed, he discovered that he was dragging a collapsed sail at two knots with sea room fast decreasing.

There is no substitute for a proper sea anchor.

They can cut drift to less than half a knot.

Clean your fuel

In foul weather, many of us rely on the engine to go upwind.

Dirty fuel stops engines so, as Ewen stresses, clean fuel is vital.

Ideally have the tanks emptied, cleaned and filled with new, clean fuel at the start of each season.

Failing that, make sure that all fuel going in your tanks is filtered and treated and have spare fuel filters and the tools to fit them to hand.

Offshore modifications

The message from our experts was that their storm preparations begin well before leaving port, with boat modifications.

Storm sails

Bob Shepton’s 33ft Westerly Dodo’s Delight has a furling genoa, but he added a furling staysail, perfect for storms and heaving to.

To avoid unbending the main then bending on the trysail in less-than-ideal conditions, he fitted a separate trysail track so it’s always bagged up and ready to go.

All Bob needs to do is douse the main, attach halyard and sheet and his trysail is as good as set.

Traditionally, trysails are loose footed with the clew led to a cleat aft.

Bob found this fine for heaving to, but it lacked drive when he wanted to claw to windward so he devised a system that lets him flatten the trysail, and ease the sail in gusts.

He runs the sheet through a block on the boom end, then runs it forward to a purchase at the mast, which also doubles as the pole downhaul.

Hull integrity

The sole is fixed and the coachroof ports reduced in size to make them less vulnerable to stoving in

Roger Taylor conceived Mingming and Mingming II for extended sea-keeping in Arctic latitudes and does much of his storm preparation at the design and build stage.

His first priority is a totally watertight yacht.

‘I replaced the sliding hatches and washboards with proper hatches and solid timber and all ports are reduced in size,’ he says.

‘The hull has ben made unsinkable with large foam-filled compartments behind watertight bulkheads fore and aft.’

Ewen Southby-Tailyour recommends heavy ‘blanks’ to protect windows.

Can you strengthen hatches and skylights?

Could your washboards survive a wave coming up astern and smashing into them?

Can the companionway hatch be locked and unlocked from both sides?

If it has washboards, is there a lanyard to prevent the washboards sliding out and floating away if inverted?

Can the lanyard be released from both the cockpit and the cabin?

Secure below

With the Crash Test Boat inverted, the chart table empties, sole panels crash around and only the gas pipe stops the stove from breaking loose

Is everything secured against inversion, from sole to salad bowl?

Anything can become a missile during a knockdown.

Read YM’s Crash Test Boat report on capsize for ideas (or buy the Crash Test iPad app for £1.49).

Bob Shepton lashes himself into his berth to stop himself falling across the cabin during an inversion

It is important that everyone stays warm and rested.

The best rest is found in bed and the best chance of staying there is to fit leecloths or leeboards.

Bob Shepton goes one further: ‘I have a ‘seatbelt’ to keep me in my berth in the event of a knockdown.’

Ewen Southby-Tailyour suggests that ‘you should have at least one manual bilge pump in the cockpit and another below, both of which can be operated with all hatches and lockers shut.’

Every pump should have its own strum box to prevent it clogging.

For all the latest from the sailing world, follow our social media channels Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Have you thought about taking out a subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine?

Subscriptions are available in both print and digital editions through our official online shop Magazines Direct and all postage and delivery costs are included.

- Yachting Monthly is packed with all the information you need to help you get the most from your time on the water.

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our expert skippers and sailors

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment will ensure you buy the best whatever your budget

- If you are looking to cruise away with friends Yachting Monthly will give you plenty of ideas of where to sail and anchor