Bob Roberts describes how the sight of a Thames sailing barge lured him back to a life afloat in this extract from his book, Coasting Bargemaster. His was the last vessel to trade under sail alone.

More and bigger ships were using the river, and once or twice I spent my spare hours walking the banks of the lower reaches, watching the interminable stream of traffic on the tideway.

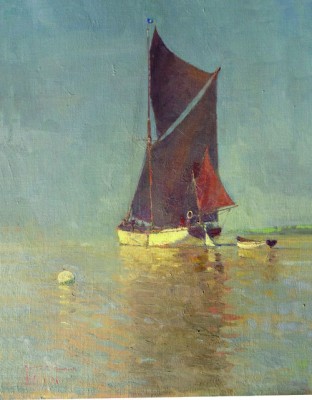

Great liners stood out like giants among the myriads of tugs and lighters, the bustling colliers from the north, the crowds of small Dutch motor ships which at that time were collaring our coastal trade with cheap freights. But it was the red-sailed sailing barges that took my fancy as they threaded their way to and fro, looking very stately and dignified amidst that horde of power- driven, smoke-grimed, soulless ruffians. For all their slab sides and flat bottoms the barges were real ships in comparison with the noisy mechanical contraptions which were forever threatening to run them down.

The amazing sailing qualities of these barges and the skill of their crews had always been highly praised by schooner men who used to come to Erith with china clay from the Cornish ports. I remember old Charlie Deacon, the veteran skipper of the barquentine Waterwitch (in which ship I had been drilled in the elements of seamanship), telling me that ‘you can’t beat a bargeman in a tideway.’ And old Charlie was reckoned pretty smart himself in close waters.

I have sat down to write this tale of sailing barges, of slashing breezes and bellying red canvas

I was standing by the lock gates of the Royal Albert Dock one day, and a grey steel barge named Reminder was waiting to go out into the river. She lay in the lock with her topsail sheet out, looking rather gawky and awkward among the bunch of craft around her. Then as the lock gates opened there came the rattle of her topsail halyard block, the screech of a brail winch, a fluttering of white canvas as the big staysail went up the topmast stay; and within a matter of moments she was a cloud of sail. All this was done by two men, the skipper and mate, an impossible feat in any other type of vessel. These barges only carry two men, except the very big ones which have three on long coastal voyages.

It was the sight of Reminder going out of the dock that day and sailing away in the sunshine down Gallions Reach towards her own peaceful Essex coast that finally put paid to my ideas of settling down ashore.

Before I quite realised what I was about, or had considered the consequences of my actions, I found myself mate of the sailing barge Audrey, trimming coal at Becton gasworks, where we were loading for Southend. And was I sorry? Well, that was a long time ago, and I’m not sorry yet. For, although the schooners were nearly all gone, here was a new life, a new world, but it was still a world of sail. And the training I had had with gaffs and booms and squaresail yards stood me in good stead in this new and complicated spritsail rig. Before a year had passed I was out of the river work: I shipped as mate in several of the big coasters that traded from London to the Humber and down Channel. And in due course I became master.

So after all these years I have sat down to write this tale of sailing barges, of slashing breezes and bellying red canvas, of a world so different from the workaday life of the ordinary citizen. I will not claim it is a pretty story of an idealistic life which will send the romantic-minded seeking a berth in a sailing barge, because such a romanticist would end up a disllusioned and embittered fool. But it is a tale worth telling for all that and I will tell it from the inside; not as an interested observer or an envious admirer, but as one who has been through the hoop and can claim, without any boastfulness or exaggeration, to have lived through the years of relentless driving, of days and nights at sea when man pits himself against the elements, not for fun or bravado, but for his very existence, and for the existence of his home and family. And it is a cruel and bitter fight.

There are, roughly, two sorts of sailing barges – coasting barges and river barges, or to be more explicit, big ’uns and little ’uns. Some of the later coasting barges such as were built in the 1920s were, as barges go, colossal things with steel hulls, capable of carrying 280 tons to sea and over three hundred on a river freight. They were quite worthy to ply with safety any of the waters of the Home Trade; that is the coast of Great Britain and Ireland, the Isle of Man and the continental coast from Brest to the Elbe. All with a crew of three.

Their flat lines are ugly and shapeless to a schooner man’s eye but have a beauty of their own when you get used to them. Instead of a keel, a barge is fitted with leeboards, which lower down on each side to prevent the barge from being blown to leeward when she is beating against the wind. The barge ‘lays’ on her leeboard and is thus pressed forward by her canvas instead of being blown broadside. There is a great art in using these leeboards, and no barge is any good without them. The great utility of a sailing barge is its combination of large capacity for cargo with exceedingly light draught and small crew.

I suppose that one day they will, like many other beautiful ships of sail, just disappear from our rivers and coasts, but they will hang on just as long as skippers and mates can be found.

– Excerpt from the book, Coasting Bargemaster by Bob Roberts