Vyv Cox explains a simple error that causes chafe on swinging moorings and catches out many crews, including experts

Wherever we sail, there is a good likelihood that at some time we will pick up a mooring. All that is needed is to pass a rope through the shackle on the top of the buoy, make it off to a cleat and take the dinghy ashore. Right? Well no, not quite that straightforward.

Most private moorings that might be picked up have a pick-up rope or chain that can be attached to a convenient cleat. Ideally this should pass over the bow roller, which may mean moving the anchor to somewhere else, either stowing it on deck or hauling it up on the pulpit. It goes without saying that when borrowing a mooring every effort should be made not to overload it and you must be prepared to move your boat if the owner returns.

Public moorings are proliferating everywhere, either to boost the economy of a local village or business, for environmental reasons where there are sensitive plants or other organisms on the seabed, or to allow more boats to berth in a given area. Some of these have pick-up ropes but most do not. Sometimes there is a light rope for convenience when first arriving, but this is often in such poor condition that it cannot be relied upon. So where there is just a big rusty shackle on top of the buoy, how should the boat be attached to it?

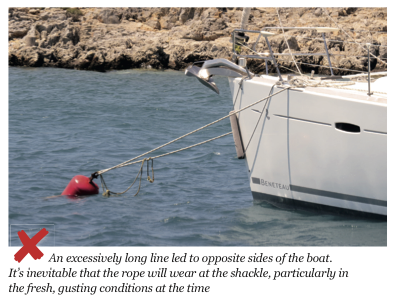

The first requirement is that it should be possible to leave the buoy with the minimum of trouble, which almost always means passing a rope through the shackle and attaching both ends on the boat. This is where so many people go wrong. There seems to be a belief that the correct way to do it is to attach the ends of the rope to cleats on opposite sides of the boat.

In any wind, the boat yaws through as much as 100 degrees, repeatedly dragging the rope through the shackle as it does so and wearing it rapidly. After only one night moored in this way, it is perfectly possible to wear through a rope of 14 or 16mm. It is vastly preferable to take both ends of the rope either through the bow roller or, to save the trouble of moving the anchor, to a fairlead or cleat on one or the other side of the boat. Wear against the shackle is now all but eliminated and can be prevented altogether by first sliding a length of plastic hose over the rope so that it sits against the shackle. The length of the rope only needs to be sufficient that the boat does not collide with the buoy and there is no advantage in making it over-long.

This technique is perfectly OK when on a charter boat but something better may be required for your own vessel. I carry a device made many years ago specifically for connecting to the Scottish Highland and Islands buoys. This is a two-metre length of 8mm chain, with lengths of 14mm rope spliced to each end. The chain lies against the buoy shackle, providing total wear protection. It also doubles as a means of untripping an anchor that has picked up a cable or heavy chain, sliding the chain down the cable from the tender, then pulling it forward. We also carry a couple of patent mooring hooks, occasionally useful in some circumstances for initial attachment to a buoy, but our experience is that in most cases there is some reason why these cannot be used, such as the shackle is the wrong size, or has line wrapped around it, or is lying on its side.

The next problem occurs when the tidal flow reverses or when the wind is light and fluky. The buoy will bang against the stem of the boat, sometimes for hours, occasionally doing some damage but always rendering sleep in the forecabin impossible. Other than fendering, probably the only possible solution in modern vertical-stemmed boats, it can help a great deal to haul the pickup rope in hard, partially lifting the buoy out of the water. In this case it is far preferable for the rope to pass over the bow roller to keep the buoy as far as possible from the stem of the boat.