On a day of light winds, taking advantage of the sea breeze can make all the difference to a coastal passage, says Ken Endean

How to understand a sea breeze

Ken Endean is an inshore pilotage enthusiast who has made a close study of coastal sea conditions around the British Isles

In a really good sea breeze, a yacht can knock off a passage of 40 miles before teatime, while the weather map’s widely spaced isobars suggest nothing more vigorous than light airs. And this is usually a splendid sail across a sparkling sea, under a hot sun, with hissing foam peeling off the lee bow for mile after mile.

Many sailing books covering meteorology concentrate on dangerously strong winds, while giving perfunctory treatment to sea breezes, probably because they are relatively benign and are only found over coastal waters, in fine weather. This emphasis is understandable, but the majority of cruising sailors spend their time on coastal waters and try to do their passage making in fine weather. Sea breezes deserve to be taken more seriously!

What is a sea breeze?

The basic process of sea breeze formation: stage 1

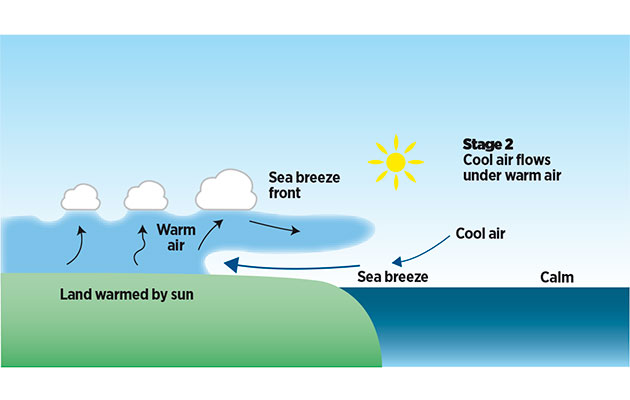

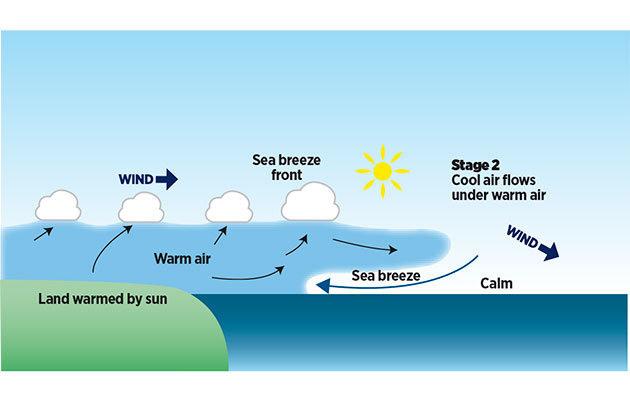

The basic process of sea breeze formation: stage 2

The diagram above shows a sea breeze being created on a sunny day, with no interference from other winds. As the sun plays on the land, it generates buoyant ‘thermals’ of rising warm air. The thermals mix with the air above so that the lower part of the atmosphere over the land becomes warmer and less dense. The denser air over the cool sea then ‘slumps’ and flows under the less dense air, pushing inland as a tongue of sea breeze. A little way offshore, there is initially an area of calm, as in the foreground of the photo above, but as the inflow intensifies it affects a wider area and the breeze is likely to eat back into this calm zone, extending its influence for several miles from the coast.

A sea breeze at an early stage of its development, off Milford Haven, Wales, blowing onto the beach but leaving a windless zone further offshore

Cumulus clouds indicate vigorous thermals – good conditions for the formation of a sea breeze. As the tip of the sea breeze tongue moves inland, it forces the warm air upward and may form a line of more prominent clouds. To seaward of this line there are fewer clouds, or even a clear sky, because the tongue of cool air has chopped off the thermals. If the seaward edge of the cumulus clouds is sharply defined, it is known as the sea breeze front. Descriptions of the sea breeze effect usually focus on rising warm air, but it is the flow of cool air that actually constitutes the breeze and produces useful horsepower for cruising sailors.

Is it affected by other winds?

Sea breeze forming against an offshore wind: stage 1

Sea breeze forming against an offshore wind: stage 2

If a wind is already being generated by large-scale weather systems – I shall call it a background wind – that will modify the behaviour of the sea breeze. A strong wind off the shore could prevent the breeze pushing inland but a light wind off the shore is more likely to merely delay its onset. At first, a mass of warmed air drifts out over the sea, as shown below. When the tongue of sea breeze finally makes its appearance, it is sliding in across the coastal water, spreading dark ripples but preceded by a zone of fluky airs and glassy waves where the original wind is lifting up.

How do I spot a sea breeze?

In its early stages, a sea breeze may flow inland as a very shallow layer of air

To anticipate the onset of this kind of breeze, watch for a dark line to seaward as the band of new ripples moves inshore. The leading edge of a sea breeze is usually quite shallow and we may be able to see this directly if it crosses an industrial site, where smoke stacks or steam vents emit plumes at various levels. High-level plumes remain in the background wind while the sea breeze changes the alignment of the lower plumes. When a sea breeze blows against the background wind, the latter re-establishes its influence further offshore, leaving a zone of calm between the two winds. The position and extent of this zone will vary during the day and present a puzzle for anyone who is on a sailing craft, hoping for a fast passage. It may be necessary to make a firm decision: either to steer inshore, hoping for a more consistent sea breeze near the land, or to head offshore and stay in the background wind.

What if a wind is already blowing onshore?

An onshore wind strengthened by the sea breeze effect

So far, I have described sea breezes as flowing masses of cool air, but it is also instructive to analyse them in terms of pressure changes. An accumulation of warm air has the effect of reducing atmospheric pressure. Therefore, when the warming of air reduces the pressure over the land, but the pressure over the sea remains unchanged, that pressure difference naturally causes wind to blow from sea to land. This helps to explain what happens when a background wind is already blowing on to the shore.

The coast of Kerry, Ireland: the light onshore wind will increase as huge cumulus clouds bulge over the land (Lemon Rock is in the foreground)

As the wind crosses the coast and passes over warm ground, thermals raise the air temperature and therefore reduce the pressure. In this case there is no sharp transition between dense and less dense air, because both warm and cool air are flowing in the same direction, but the reduction in pressure over the land exerts more ‘pull’ on the air that is over the sea, causing an increase in the wind strength across the coast. A background wind that is reinforced in this manner may become strong enough to cause difficulties for small boats.

Why does it sometimes change direction?

A developing sea breeze, penetrating inland and veering during the day: late morning

A developing sea breeze, penetrating inland and veering during the day: late afternoon

As soon as any wind starts to blow, from high pressure towards low pressure, the Earth’s rotation compels it to change direction. This is known as the Coriolis effect. In the northern hemisphere, the change of direction is a veer to the right, so that the wind vector has low pressure on its left.

When a sea breeze develops during a fine day, an accumulation of warmed, less-dense air causes a progressive drop in atmospheric pressure over larger areas of the land. Local sea breezes form over peninsulas and coastal islands but later merge into a general airflow towards the larger landmass that lies beyond. While the breeze is strengthening, the Coriolis effect changes its direction and it veers so that the low pressure is on its left. Thus, the sea breeze may begin by blowing directly on to the land but end the day blowing parallel with the shore.

Geographical features modify and deflect sea breezes. A shallow layer of breeze will flow readily on to a low coastal plain but may not be able to rise over high cliffs. If the breeze is channeled up a valley, constrained by the valley sides, it will resist the normal tendency to veer during the day.

When sea breeze fronts move well inland, the sea breezes from different coastlines will coalesce, as shown in the diagram above. In this example, the fully developed breeze cuts across the peninsula. On the eastern side, the late afternoon wind is coming off the land, but it is nevertheless a sea breeze, blowing over from the opposite coast.

When planning a cruise around a large island, such as Britain or Ireland, sea breezes will normally be more favourable during an anti-clockwise circumnavigation (in the northern hemisphere).

How strong can it get?

A wind blowing parallel to a coast becomes stronger if daytime warming reduces pressure over the land and intensifies the pressure gradient

The lines indicate isobars

The strongest winds are generated when a day begins with lower pressure over the land than over the sea and the isobars lie parallel to the coast, so the background wind is blowing along the shore (with the land on its left, in the northern hemisphere). If the sun warms the land and leads to a further reduction in pressure, that process simply intensifies the pressure gradient, cramming the isobars closer together and cranking up the wind strength (see diagram, above right. This effect is quite common at convex coastlines with low hinterlands and I have experienced particularly vigorous blows off the low coast of the Vendée, in western France.

Perfect offwind sailing with the Biscay sea breeze providing plenty of horsepower. An hour later it had risen to a Force 6

On one occasion, the day started with a wind of Force 3, but this later increased until sustained anemometer readings of 32 knots (on a boat sailing downwind) suggested that the wind was at least Force 7, and the French coastguard service issued a gale warning.

The sea breeze effect should never be underestimated and is sometimes capable of producing a moderate degree of violence. The good news is that the strongest winds will only persist for a short time, fading before the waves have become fully developed.

If such a wind creates intimidating conditions, perhaps when a boat is approaching a tricky harbour entrance, the problem can probably be resolved by standing offshore for a couple of hours until the breeze loses some of its strength.

Does the season affect sea breeze?

The sea breeze effect is stronger in spring than in autumn, and this is usually attributed to the greater temperature difference between the warm land and the cool sea during the spring months. Another explanation is that in late summer, the atmosphere is generally warmer than in early spring, so we should expect fine-weather thermals to be less vigorous, irrespective of sea temperature.

Why might the sea breeze fail to appear?

Sea breeze formation prevented by a stable lower atmosphere

On some summer days, the sun rises into a cloudless sky and the temperature climbs rapidly, but the sea breeze stubbornly refuses to put in an appearance and the sky remains cloudless. It may be that, during a period of fine weather with anticyclonic subsidence, the atmosphere has become warmed to a considerable height. After a clear night, there is probably a shallow layer of cool air close to the ground, creating a temperature inversion. Daytime thermals can rise through this layer but will stop or slow down when they meet the warmer air immediately above, so the mixing and warming process is curtailed.

Rising air creates wispy traces of cloud but the atmosphere is too stable for vigorous thermals and cumulus clouds, so the sea breeze is feeble

Normally, thermals are boosted by moisture condensing into clouds and releasing latent heat, but if the atmosphere is both warm and dry, there is not enough moisture to condense into clouds and therefore no boost. These atmospheric conditions are inherently stable and also occur when a deep mass of warm air drifts from the middle of a hot continent. Glider pilots, who use thermals to gain height, know they’re unlikely to experience good soaring conditions in Britain when a southerly background wind is bringing warm air from mainland Europe.

What happens to a sea breeze at night?

In Worbarrow Bay, Dorset, high cliffs overlooked by steep hillsides can generate katabatic gusts on clear nights

As sea breezes depend upon the sun’s warmth, they inevitably die in the evening, or earlier if clouds move across the sky. However, at night, if the temperature of the land drops below that of the sea, it is possible for the sea breeze effect to be reversed, causing a land breeze that blows off the shore. Most are weak, but where cool, dense air is able to flow smoothly down a valley, it should be sufficiently strong for early morning sailing. However, such breezes generally extend only a mile or two offshore and die as soon as the sun warms the land.

Where the land slopes steeply, and particularly when there is a very clear night sky so that the ground loses heat rapidly by radiation, the land breeze can be much more vigorous – even violent. This is known as a katabatic wind, sometimes taking the form of a stiff wind blowing out of a valley, or sudden avalanches of cool air sliding down the slope of a mountain or high cliff before bursting outwards over the sea – rather alarming if a boat has anchored in what looks like a quiet bay, at sunset, and the crew are expecting a peaceful night! They may draw comfort from the fact that the wind is blowing off the shore and should not create any large waves.

How does the sea breeze affect where I should anchor?

To answer this question, we need to understand the full sea breeze cycle. In the diagrams below, we have a south-facing coast with a projecting peninsula and three possible anchorages.

A typical sea breeze cycle, showing the benefits of different anchorages: dawn

Dawn – the background wind is from the north-east, so that anchorages A and C are sheltered but B is exposed.

Late morning

Late morning – sea breezes develop on each side of the peninsula and all three anchorages experience an onshore wind.

Late afternoon

Late afternoon – now the sea breeze has pushed inland and veered, so anchorages B and C are sheltered.

Night

Evening and night – if the background wind is feeble, all the anchorages will be quiet overnight, possibly with light land breezes where valleys encourage the cool air to flow downhill.

If a vigorous background wind returns when the sea breeze dies, as shown in the fourth diagram above, anchorage B will again become uncomfortable – or even dangerous, depending on the wind strength and the length of the wave fetch. Anchorage A will be sheltered from the background wind but may experience several hours of short swell from waves that were created by the afternoon breeze. In those circumstances, anchorage C is more suitable for overnight shelter.

On the southern side of Ile Hoëdic, in North Biscay, the boats are sheltered from the northeasterly wind and the long reef will provide protection when the sea breeze comes in from the west

I have done a good deal of sailing off the south-facing coasts of England and Brittany, where sea breezes from the southwesterly quadrant are common in fine weather, when the background winds are often from the north or north-east. In those circumstances, the best anchorages for fine weather are usually those sheltered from both the west (for the afternoon) and north (for the night).

A short daysail, helped by a sea breeze

Lyme Regis harbour is a convenient refuge in the middle of Lyme Bay

In the wide, curving inlet of Lyme Bay, thermal effects usually bend the summer winds, although the geography is not ideal for creating strong sea breezes. Along much of the shoreline, cliffs or steep hill slopes rise straight from the beach, with a few narrow river valleys leading through this natural wall. From time to time, full-blooded sea breezes climb over the wall and surge inland, but on other occasions a background wind blows out of the valleys and tussles with the sea breeze, so that the inshore winds become variable.

A short coastal passage, in a wind veered by the sea breeze effect

We wanted to make a short, 25-mile coastal hop, from the River Exe eastward to Lyme Regis. Time was of the essence – we needed to arrive while there was enough depth of water to enter the drying harbour.

On the day of the passage, which is shown in the diagram below, the forecast wind was east or north-east, Force 2–4 becoming variable, suggesting a painfully slow beat, dead to windward.

The early morning breeze on the Exe estuary was actually northerly, Force 2-3, as cool air formed a gentle katabatic flow down the valley and pushed us out of the river, against the flood tide.

Off the River Exe entrance, the valley wind died in fluky puffs and we met the background wind – east-north-east, Force 3 or 4 – and short, choppy waves.

Too close inshore, winds may be fluky, while a little further out you can set sail

We were tempted to tack inshore, in search of flat water. However, weather conditions on the previous day had been almost identical, under partial cloud cover. In the bay, the wind had displayed a sea breeze shift, slowly veering to the south-east and blowing more directly onshore as the land warmed up, although it had not undergone the full veer to the south-west that sometimes occurs in very fine weather.

We therefore kept on port tack, working gradually out into the bay and hoping for a similar veer. Although initial progress was slow, patience began to pay off at 1100 when the wind veered towards the east, becoming fitful for a while, whereupon we finally tacked.

Over the next couple of hours, the wind continued to veer and then strengthened, eventually becoming a good south-east Force 4, so that our approach to Lyme Regis turned into a storming close reach, steering a course that was directly into the original wind direction. There was ample time to enter harbour before the tide fell.

For most of the passage, the boat had been sailing close-hauled and yet the ground track covered was only slightly longer than the straight line distance. If we had tacked inshore earlier, we would probably have encountered more fluky conditions because northerly winds, blowing down the river valleys, will often persist for several hours against an

incoming sea breeze.

Another yacht, which arrived at Lyme Regis about an hour after us, had motored right around the bay, close to the land, with wind on the nose for almost the whole way, and was running short of fuel.

Enjoyed reading How to understand a sea breeze?

A subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

YM is packed with information to help you get the most from your time on the water.

-

-

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our experts

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment

- Cruising guides to help you reach those dream destinations

-

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.