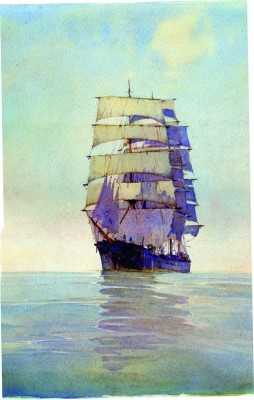

Any skipper embayed on a lee shore needs a steady nerve. Alan Villiers recalls his experience on a Tall Ship that couldn’t beat to windward, as the barometer took a plunge.

Sixty-two days out from Tocopilla, Chile, the Pitlochry, a four-masted barque, 319ft long, was off Terschelling, having breasted a Force 8 gale up the English Channel dashing along at 16 knots for her penultimate leg. But there the wind died, for the depression was racing by. The barometer had gone down steadily. Now it stopped. The Pitlochry was right in the centre of the depression: there would soon be wind enough again very soon.

I had noticed as we came through the lower North Sea off the coast of Holland how extraordinarily clear the air was, with exceptional visibility. The coast is sandy, low and plain, but it looked as if it had been raised and somehow, though so unusually clear, further away. I knew this was a bad sign. It could mean that a heavy storm would follow. We lay becalmed.

The very low barometer was giving us excessive long notice of something nasty coming up. What I wanted to do, of course was to get safely into the Elbe with the first of it – anchored and safe. What we got at first was a few hours of almost doldrums conditions, cat’s paws from all around the compass – nothing steady.

The ship jumped about in an unnatural swell, the sails banging back against the masts and the chain sheets rattling, and everybody getting a little on edge, just outside our home port more or less and just not getting anywhere. It was eerie. It took real stagnation to stop our Pitlochry, she really was one of those ships that seemed to be able to give herself steerage way with the flap of her sails.

‘The very low barometer was giving us excessive long notice of something nasty coming up’

But for much of that day she didn’t steer. What was very odd about it all was that we saw no other ships. Where were they all? This was one of the busiest sea areas in the world, yet only we were there. I guessed the storm signals must be flying at every harbour mouth for a hundred miles around. There was no sign even of a fishing boat. The North Sea was empty. There were no special signs I could read in the sky – only threat.

It was winter. The day was short. The glass stayed very low, without movement. We slipped into the night with a breath of southerly air – just a breath that only the Pitlochry could find over that dull, dead sea. Then a calm spell again, then a little breath of wind out of the north.

The wind freshened from the northwest as if it was just getting together in this place all its tremendous breath, whistling down from Iceland. I put her on the port tack, to be safer when the gale came. Then a hard squall of hail hit her and the wind leapt to gale force. The sails were like great black shapes of steel.

There was no sign of any pilot boat. I realised we had made so fast a passage that the office wouldn’t be expecting us. It howled up to Force 10, gusting to eleven. Nobody could tack in that sort of wind. I couldn’t wear either, there was not enough room. I had to run into the Elbe.

The river mouth is well marked. Light vessels Elbe 2 and Elbe 3 flashed by, then everything was blotted out in one great mad shrieking of the wind. Now not just hail struck me. Sand was flying through the air, it struck my face. It was like being sandpapered. The wind screamed at the rigging screws hauling 3,000 tons of ship and 4,000 tons of nitrate. We were making 18 knots over the ground.

The Mittelrug bank lay right in the river. Lightship Elbe 5 marked the place for course alteration to clear it. Deeper-draught vessels must leave Elbe 5 to starboard.

Elbe 5 was in sight.

‘Hard a-starboard!’ Down spun the wheel. ‘Let go anchors’.

As fast as the crew tried to check them, both cables jumped right out of their grooved drums with sparks and noise and rushed out through the hawse pipes – 150 fathoms of cable on each anchor. The cables stood out like violin strings. Thank God they stood.

Soundings showed the least depth at low water gave Pitlochry a fathom under her keel – not much but enough.

In the morning, the timid light of frightened day showed the buoy marking the Mittelrug Sand 50 yards astern.

– Excerpt from the book, The War With Cape Horn, by Alan Villiers